Jewelry design, with its evocative forms, is not only an artistic expression but also a strategic asset that must be protected through intellectual property rights. Trends change rapidly, but imitations proliferate just as quickly. Before exploring how to protect jewelry today, it is useful to look to the past to understand how these pieces have acquired such deep meaning for humanity.

The "magical" jewelry of the ancient world

Since the earliest days of human civilization, jewelry has assumed a far deeper role than one merely associated with vanity or beauty. In Mesopotamia, around 4,500 years ago, the gold diadem of Sumerian queen Puabi was not just a symbol of royal power but also a true spiritual declaration. This headdress, from the Royal Tomb of Ur, represents one of the earliest examples of how the elite used jewelry to communicate their connection with the divine.

Closeup of Queen Puabi’s gold headdress and gold jewelry, Mary Harrsch CC BY 2.0

At the same time, in ancient Egypt, pharaohs wore lapis lazuli bracelets and gem-inlaid accessories not only for their beauty but as talismans, believed to provide protection and guarantee rebirth in the afterlife. This is also why the scarab symbol was used. The Egyptians, observing the dung beetle, believed that these insects were spontaneously born from the sand. This belief arose because the scarabs seemed to emerge directly from the ground, especially after laying their eggs inside the dung balls they rolled, pushed, and buried in the sand.

The jewelry of Pharaoh Tutankhamun, first uncovered in the summer of 1922 by archaeologist Howard Carter, tells us not only about phenomenal craftsmanship in goldsmithing but also about Egyptian cosmology, where life and death were intertwined in an eternal cycle. As archaeologist Zahi Hawass explains, Egyptian jewelry served as connections to the divine: every stone held a sacred meaning, and every shape symbolized protection (see “The Golden Age of Tutankhamun” by Z. Hawass).

Winged scarab Tutankhamun’s pedant (XVIII dinasty) – Source: Wikepedia, Egyptarchive.co.uk

Moving forward a few centuries, in the Persian Empire of the Achaemenid period (550-330 BC), the use of jewelry as symbols of power offers an equally rich and fascinating expression. Achaemenid bracelets, often depicting lion or sphinx heads, were not merely accessories but symbols of strength and dominance. Worn by nobles and warriors, these jewels told stories of gods and, most importantly, of conquest.

Open-circle bracelet with lion-head terminals, from the Tehran Museum to the Aquileia exhibition of 2016 – Source: Archeologiavocidalpassato.com

In telling these stories, what emerges is a common thread: jewelry is not merely ornamental but powerful instruments of cultural communication. Through them, ancient civilizations told stories of identity. Even today, by visiting museums or reading about these discoveries, we can understand how these creations continue to speak to us, not only about the past but also about our enduring need for beauty and, above all, meaning.

While in antiquity jewelry was often a means of divine connection and spiritual status, during the Renaissance in Europe, these objects transformed into tools of political manipulation and symbols of courtly intrigue.

Jewelry as a symbol of nobility, intrigue, and political manipulation

During the Renaissance and the centuries that followed, jewelry was not simply a luxury adornment, but a subtle tool for manipulation, influence, and even deceit. But let’s proceed step by step.

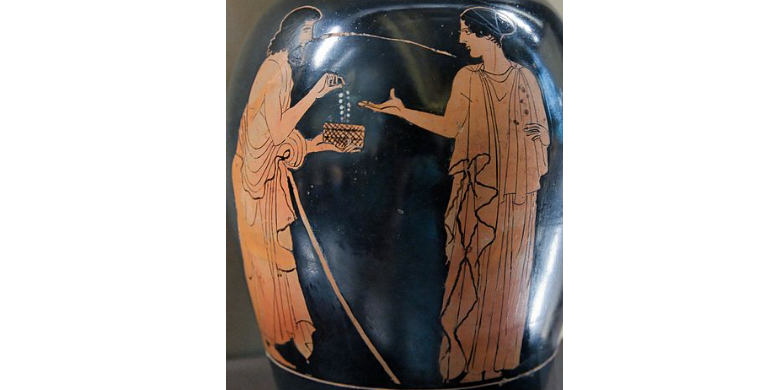

In Greek mythology, the archetypal example of these “dances of power” is the golden necklace of Harmonia. Although it did not truly exist, the necklace of Harmonia, gifted by the goddess Aphrodite to Harmonia for her marriage to Cadmus, is often cited as a symbol of beauty that hides a curse within.

The magical necklace allowed any woman who wore it to remain forever young and beautiful, making it highly coveted. However, it is said that the necklace brought misfortune and tragedy to whoever possessed it. In fact, both Harmonia and Cadmus were transformed into serpents and, as the necklace changed owners, it gave rise to further myths and legends.

Polynices gives the necklace of Harmonia to Eriphyle, Red-figure Oinochoe, ca. 450–440 BC, Louvre Museum – Source: Wikepedia

From Greek myths, we move to the Italian Renaissance, where jewelry became instruments of power in the courts. The Medici family of Florence used jewelry to display wealth and solidify political alliances. Eleonora of Toledo, wife of Cosimo I de’ Medici, often portrayed wearing a necklace of emeralds and diamonds, symbolized not only her status but also the authority of the Medici family. The Medici’s signet rings, used to seal documents, were further symbols of power.

The Borgias, known for their political scheming, used jewelry as strategic gifts to build alliances. Lucrezia Borgia owned numerous pieces of jewelry, including necklaces and bracelets adorned with rubies and sapphires, often used to seduce or negotiate. The Gonzaga family of Mantua, represented by Isabella d’Este, renowned for her collection of diadems and gems, used jewelry to enhance their status.

Detail of the “Portrait of Isabella d’Este” by Titian (1536) – Source: Wikipedia

These pieces of jewelry were often commissioned from the finest goldsmiths of the time and served not only as symbols of refined taste but, above all, as a testament to one’s status. Medallions and cameos, featuring erudite and allegorical symbols, were frequently exchanged among nobles to signify friendship or to consolidate alliances.

Even in the European courts of the 18th century, jewelry continued to be powerful symbols, capable of consolidating or toppling entire dynasties of rulers.

Marie Antoinette, Queen of France, is one of the most iconic examples of how jewelry could ignite scandals with devastating political consequences. The case in question is known as the affair of the diamond necklace: an extraordinary jewel, originally designed by two Parisian jewelers for Madame Du Barry.

The Diamond Necklace – Reconstitution – Source: Worldinparis

The necklace, composed of 647 diamonds, was originally commissioned by King Louis XV for his mistress, Madame du Barry. However, by the time of the king’s death in 1774, the necklace had not yet been completed. The price of the necklace was astronomical, and the jewelers, Charles Böhmer and Paul Bassenge, were left with the valuable piece unsold. The jewelers attempted to sell the necklace to the new queen, Marie Antoinette, who declined the purchase, deeming it too expensive and out of line with the economic climate of the time.

But Jeanne de La Motte, a fallen noblewoman and skilled swindler, intervened, pretending to be a close friend of the queen. Jeanne orchestrated a complex scheme to deceive Cardinal de Rohan, an influential member of the court who sought to redeem himself in the queen’s eyes after falling from grace. Jeanne convinced the cardinal that Marie Antoinette secretly desired the necklace and that, if he purchased it for her, he would regain her favor. Deceived by Jeanne, Cardinal de Rohan contacted the jewelers and offered to buy the necklace in the queen’s name. A night-time meeting was arranged where a woman resembling Marie Antoinette (in fact, a prostitute named Nicole Le Guay) met the cardinal and handed him a forged letter confirming the purchase of the necklace. After receiving the necklace, Jeanne de La Motte and her accomplices dismantled the jewel and sold the diamonds separately to various jewelers for money. When jewelers Böhmer and Bassenge did not receive payment, they approached the queen, who denied ever having ordered the necklace. This led to a scandal. The affair culminated in a public trial in 1785. Cardinal de Rohan, unaware of the deception, was arrested. Jeanne de La Motte was also arrested, tried, and convicted of fraud, but Marie Antoinette’s reputation took a devastating blow. Many French people, already inclined to believe rumors of the monarchy’s excessive luxury and corruption, saw this scandal as confirmation of the court’s moral decay, contributing to the growing discontent that led to the French Revolution on May 5, 1789.

Crowns, tiaras, and necklaces adorned the heads — and necks — of rulers, imbuing them with obvious political significance. Kings and queens used jewelry as diplomatic gifts or tokens of alliance, giving these objects the power to forge or break ties between nations.

In England, the crown of Elizabeth I (1533-1603) was not only a symbol of sovereignty but also a means of communicating her status as the “Virgin Queen“, subject to no man’s power. Every gem and pearl set in her crown carried a message: purity, divinity, and the ability to govern.

Painting of Elizabeth I of England, also known as the Ermine Portrait – Source: Wikipedia

Her image, immortalized in portraits adorned with sumptuous jewelry, became a visual manifesto of her reign. The pearl necklace gifted to her by the pope, for example, symbolized not only her purity but also a challenge to the Catholic powers of the time. In an era where religious wars and political alliances were commonplace, every piece of Elizabeth I’s jewelry was a calculated symbol of her power, independence, and ability to rule without the influence of a male consort.

In European courts, jewelry thus became essential tools for projecting power and solidifying political bonds. From the Medici to the Borgias, from the Gonzagas to Elizabeth I, jewelry was not just an expression of luxury, but a true declaration of political intent. Through the strategic use of crowns, necklaces, rings, and brooches, noble houses conveyed complex messages of authority, alliance, and dominance.

These examples remind us that jewelry was much more than mere adornment. It was a tool of political communication, capable of telling stories of ambition, passion, and intrigue. Worn by the most powerful men and women of their time, jewelry became vehicles of power — sometimes blessed, other times cursed, but always central to the narrative of royal dynasties. Precious stones and metals not only reflected light but also the dark ambitions and power plays that shaped the destinies of many European courts.

Today, as we contemplate these jewels in museums, we can only sense the echo of the decisions, alliances, and schemes of which they were witnesses, and sometimes even protagonists. With the advent of the modern era, the significance of jewelry has shifted from the realm of royal politics to that of the collective imagination, becoming powerful symbols in cinematic and literary stories.

That inexplicable human desire to possess them

Jewelry — especially when rare, unique, or lost — has always captured the human imagination, becoming symbols of love, power, and mystery. It is no surprise that, from literature to cinema, these objects have become central to legendary stories that transcend their material value, turning into true pop icons.

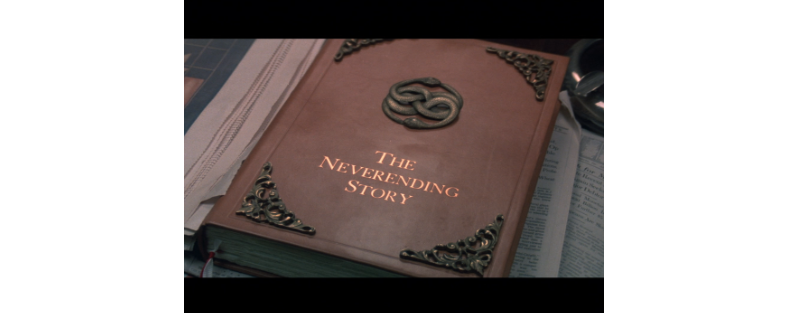

One of the most iconic pieces of fantasy jewelry is the Auryn from Michael Ende‘s The NeverEnding Story. This amulet, with its two intertwined snakes biting each other’s tails, represents infinity and absolute power. In Ende’s universe, the Auryn is not just a valuable object but a talisman that protects its bearer and symbolizes the authority of the Childlike Empress. In the 1984 film directed by Wolfgang Petersen, the Auryn captures the audience’s attention, embodying the adventure and courage that guide the protagonists, Atreyu and Bastian, on their fantastical journey, where each serves as a mirror for the other.

Still from The NeverEnding Story (1984) – directed by Wolfgang Petersen

Another example that captivated audiences is the One Ring from J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. This simple ring, forged by Sauron to dominate all other Rings of Power, is at the heart of one of the most epic battles between good and evil. It represents the lust for power and corruption: anyone who wears it is inevitably enslaved by it. In Peter Jackson’s films, the Ring is portrayed with brilliant simplicity: a golden circle, seemingly harmless, yet capable of exuding an aura of dark power that permeates every scene in which it appears. Its simplicity and the elusive engravings amplify its significance, making it one of the most powerful symbols in contemporary storytelling: «One Ring to rule them all, One Ring to find them, One Ring to bring them all, and in the darkness bind them».

The One Ring, in the film The Fellowship of the Ring directed by Peter Jackson – Source: Wikipedia

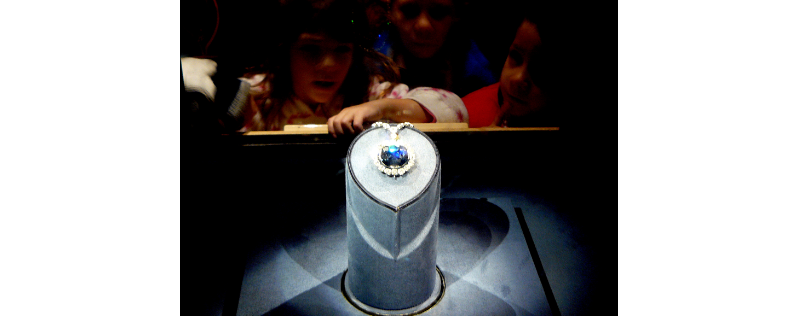

In cinema, the “Heart of the Ocean” from Titanic is another unforgettable piece of jewelry. This legendary blue diamond, inspired by the famous Hope Diamond, is at the center of the 1997 film directed by James Cameron. A symbol of the forbidden love between Jack and Rose, the “Heart of the Ocean” becomes a symbol of romantic love and the tragedy that befalls the Titanic and its passengers. When Rose throws the jewel into the ocean at the end of the film, the act represents both a release from regrets and a gesture of eternal devotion. The “Heart of the Ocean”, with its deep and sparkling blue, has left an indelible mark on pop culture as a symbol of love that defies conventions, survives tragedy, and becomes priceless.

Hope Diamond – Smithsonian museum of natural history – Source: Wikipedia

These jewels, from literature to cinema, represent universal themes — from power to corruption, from love to sacrifice. It is through their stories that these objects are transformed into cultural icons, capable of evoking deep emotions and capturing the imagination of all. The allure of these jewels lies in their ability to intertwine with human emotions and to be continuously reinvented through visual media and fantastic narratives. It is this ability to transcend their material value that makes them eternally fascinating and an integral part of the collective imagination.

Just as jewels in cinema have become symbols of power and mystery, in the real world luxury jewelry carries an even more tangible significance: they are strategic assets that require legal protection to preserve their value and uniqueness.

Originality, trends, and legal battles in the world of jewelry

Jewelry, both in the past and today, tells powerful stories of beauty, status, and identity. Each piece is more than just an ornament: it is a work of art that can become iconic, partly due to its unique design and who wears it. In the context of a global and highly competitive market, intellectual property protection is essential to defend the uniqueness of one’s creations. Some pieces of jewelry, more than others, thanks to their recent history, highlight the importance of protecting design.

Grace Kelly, Princess of Monaco, did not wear a tiara at her 1956 wedding, but instead a delicate floral headpiece embroidered with pearls and lace. However, after her marriage, Grace often wore stunning jewelry, including the Bains de Mer Tiara, an elegant piece designed by Cartier that could be transformed into a necklace or brooch. This tiara embodies the princess’s refinement and style, contributing to her image as an icon of elegance (see Preziosissima Cartier, la storia della tiara Bains de Mer di Grace Kelly on Harper’s Bazaar).

The Cartier Halo Tiara, on the other hand, was made famous by the Duchess of Cambridge, Kate Middleton, who wore it at her wedding in 2011. This tiara, commissioned by King George VI for Queen Elizabeth (the Queen Mother), embodies elegance and sophistication and has become a design icon (for further details, see L’affascinante storia della Cartier Halo, la tiara tramandata dalle donne della royal family on Harper’s Bazaar).

Another iconic piece from the British royal family is the Lover’s Knot Tiara, worn by both Princess Diana and Kate Middleton on various occasions. This masterpiece, featuring love knots and dangling pearls, was originally commissioned by Queen Mary in 1913.

Similarly, Bulgari’s Serpenti Necklace, made famous by Elizabeth Taylor in the 1960s, has evolved from a classic design into a contemporary icon, also worn by stars like Rihanna and Zendaya (see From Elizabeth Taylor To Zendaya, Bulgari’s Serpenti Has Been Seducing The Stars For 75 Years on Vogue). In such cases, trademark and design registration is essential to preserving the brand’s exclusivity and prestige.

Pandora has also often faced serial imitators of its charms. For Pandora, protecting design rights through registration has thus become a priority.

As I pointed out in a previous article, the importance of protecting a piece of jewelry by registering its design is inversely proportional to the intrinsic value of the object itself (for further details, see: “What should jewelry designers know about design law today?” by A. Canella). Relying on copyright alone is not always sufficient to protect jewelry. Registering designs is essential to prevent plagiarism and to maintain creative control over one’s work. This approach allows designers to defend the value and the story behind each piece of jewelry, preserving the artistic integrity of their work.

Some jewelry pieces, thanks to their original form and the brand they are associated with, can captivate public attention and create market trends. For this reason, it is crucial to pay attention to registering and protecting one’s original collections.

Contemporary examples, such as Meghan Markle’s engagement ring, which uniquely combines diamonds from Diana’s collection with other stones, show how jewels can be reinvented in designs that blend tradition and modernity (see “Beatrice of York, Kate Middleton, Meghan Markle: The Most Beautiful Royal Engagement Rings”). The Cartier Halo Tiara, also worn by Kate Middleton, represents another story where design becomes a symbol of elegance and historical continuity (see “Kate Middleton, Grace Kelly: Their Wedding Dresses Are the Most Copied” on Vogue).

The legal protection of jewelry and accessories in the contemporary world largely depends on intellectual property through the registration of designs and trademarks. It is essential to ensure that innovative creations, as they transform into trends, reward the designers and brands that created them, allowing them to continue telling unique and memorable stories.

From antiquity to the present day, the design of jewelry and accessories continues to fascinate humanity. From ancient diadems to contemporary masterpieces, jewelry represents a bridge between past and future, continuously enchanting, evoking emotions, and inspiring new original creations that deserve to be legally protected as well.

© Canella Camaiora S.t.A. S.r.l. - All rights reserved.

Publication date: 25 September 2024

Last update: 7 May 2025

Textual reproduction of the article is permitted, even for commercial purposes, within the limit of 15% of its entirety, provided that the source is clearly indicated. In the case of online reproduction, a link to the original article must be included. Unauthorised reproduction or paraphrasing without indication of source will be prosecuted.

Arlo Canella

Managing Partner of the Canella Camaiora Law Firm, member of the Milan Bar Association, passionate about Branding, Communication and Design.