This paper addresses the issue of artificial intelligences (capable of creating images from simple text prompts) and their possible misuse of the intellectual property rights of illustrators and other authors. In this article:

Creating original illustrations from simple text prompts

Software that allows you to create original images from simple text prompts, such as Dall-E and Midjourney, are progressively growing in popularity and use by the public and beyond.

Few people know that in order to create the images, these tools rely on huge databases of works and images of other authors, which are indispensable for making the programme work.

Professionals in the field, be they jurists, computer scientists or even art critics, being focused on analysing the potential of the tool and what the potential rights of artificial intelligence might be, overlook a crucial issue. Focusing on the ‘new rights’, those related to the newly created work, is a logical step. Nevertheless, it is also necessary to focus on the infringed rights.

Robots, authorship and award-winning work

In February 2022, the US Copyright Office rejected an application to register Stephen Thaler’s work entitled “A Recent Entrance to Paradise“.

The reason for the rejection was that the image, being created by an artificial intelligence, was “lacking the requirement of human authorship, which is essential to obtain copyright”.

A few weeks ago, another work created by an artificial intelligence even won first prize in an art competition. It was “Théâtre D’opéra Spatial“, a work exhibited at the Colorado State Fair and signed “Jason Allen via MidJourney“.

The artwork made quite a stir because artist Jason Allen used MidJourney to create it: as mentioned above, a programme based on artificial intelligence that is able to generate images from simple text prompts. All in all, neither technological skills nor drawing experience were necessary for Jason Allen.

These are just some of the cases that sparked controversy and attracted public attention. Several questions have also arisen concerning copyright and the professional future of illustrators. In other words, can illustrators oppose the forthcoming advent of robots or will they lose their jobs?

What are the real capabilities of a robotic artist?

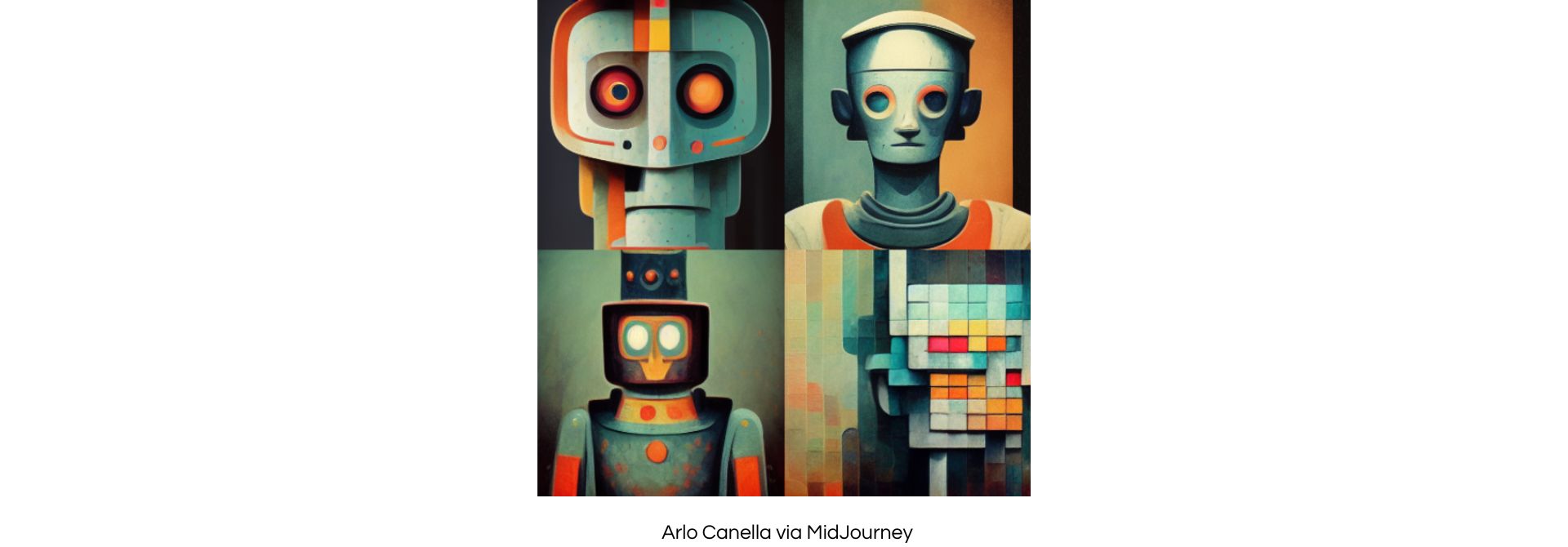

Technology-wise, jurists have experienced similar problems with the rise of photography or digital graphics, so the urge to downplay the problem is very strong. I myself gave it a try with Midjourney, and I can assure you that the result was truly astonishing. I ran the following text prompt “what are the real capabilities of a robot-artist” and got the illustration below.

Once the work was realised, however, some questions arose. According to copyright law, only the author, i.e. the human person who created the work, has the right to reproduce and commercially exploit it. Since a robot created it, copyright cannot exist and the work would formally be in the public domain.

A machine, no matter how complex, executes a human’s command in the form of a code or algorithm. It is not able to think and therefore could not fulfil the originality requirement of, for instance, the Berne Convention (also known as the Universal Copyright Convention).

The idea that a machine could be granted copyright protection is simply absurd and would create more problems than it would solve. At most, one could think of introducing a law in the future to grant this right to the owner of the software or the person who issues the text prompts to the machine. In this regard, the debate is still open.

The crucial role of "data" in the artificial creation process

Artificial intelligence-based software – in order to function – thrives on huge image databases. We do not know exactly what content is fed to these astonishing technological creatures. It seems undeniable that it can only be “data”… such as photographs, drawings or illustrations of which other (human) beings are clearly the authors.

The need for and collection of data that is indispensable for artificial intelligence software to function is usually referred to as “data mining“.

In Europe, within the framework of Directive No. 2019/790/EU, it has been decided that the benefits of the emergence of artificial intelligence are, in any case, a good thing for the citizens of the Union and that it is therefore right to limit the rights of authors (and not only those) in order to ensure scientific-technological progress.

The European legislator expressly addressed the issue of data mining in Articles 3 and 4 of Directive No. 2019/790/EU. In particular:

- Article 3 speaks of “text and data mining for scientific research purposes“,

- while Article 4 “exceptions or limitations for the purposes of text and data mining“.

Well, Article 4 of the directive is not at all clear because it provides verbatim that: “The exception or limitation [ed. of copyright and related rights] shall apply on condition that the use of the works and other subject matter referred to in that paragraph has not been specifically reserved by the rightholders in an appropriate manner, such as through means allowing automated reading in the case of content made publicly available online“.

So it seems that authors can rest easy by simply declaring – in a technologically machine-readable way – that the ‘data’ is confidential (all rights reserved ©). By doing so, data mining, i.e. the extraction of drawings, will not be permitted by law. Will this really be the case? Would the will of the authors be respected?

The silent exploitation of authors' creations

We have seen how the artificial creation process involves the use of many author images. However, as no transparency exists as to what has been extracted in data mining, there can be no certainty of infringement.

Even if an author had properly reserved his copyright – as provided for in Article 4 – there would be no way to legally access the databases to check that the robots respect the authors’ wishes.

On top of that, the robots are set up to only use small fragments of works and, in any case, to render the contributions of individual authors unrecognisable. Since the individual contribution or work is not recognisable, it is difficult for the author to be aware of the infringement and take action to check. The unauthorised exploitation of his creative work will take place silently and on a massive scale.

This approach cannot therefore exclude copyright infringement. The right will in fact be infringed in any case by the mere fact that the machine has ‘reproduced’ (in its databases) the work: the right to reproduce the work is an exclusive right reserved by law to the author alone. The only apparent legal limitation relevant for our purposes would seem to be the exception described in the previous paragraph (the one provided for data mining, see Articles 3 and 4 of Directive No. 2019/790/EU as adopted by the individual national laws).

At the end of the day, the clear result of this reasoning is that massive abusive exploitation to the detriment of authors may currently be taking place.

Spider-Man and the case of the unauthorized exploitation of fictional characters

We have thus seen how the original work and its author seem to disappear altogether once “chewed up and digested” by artificial intelligence.

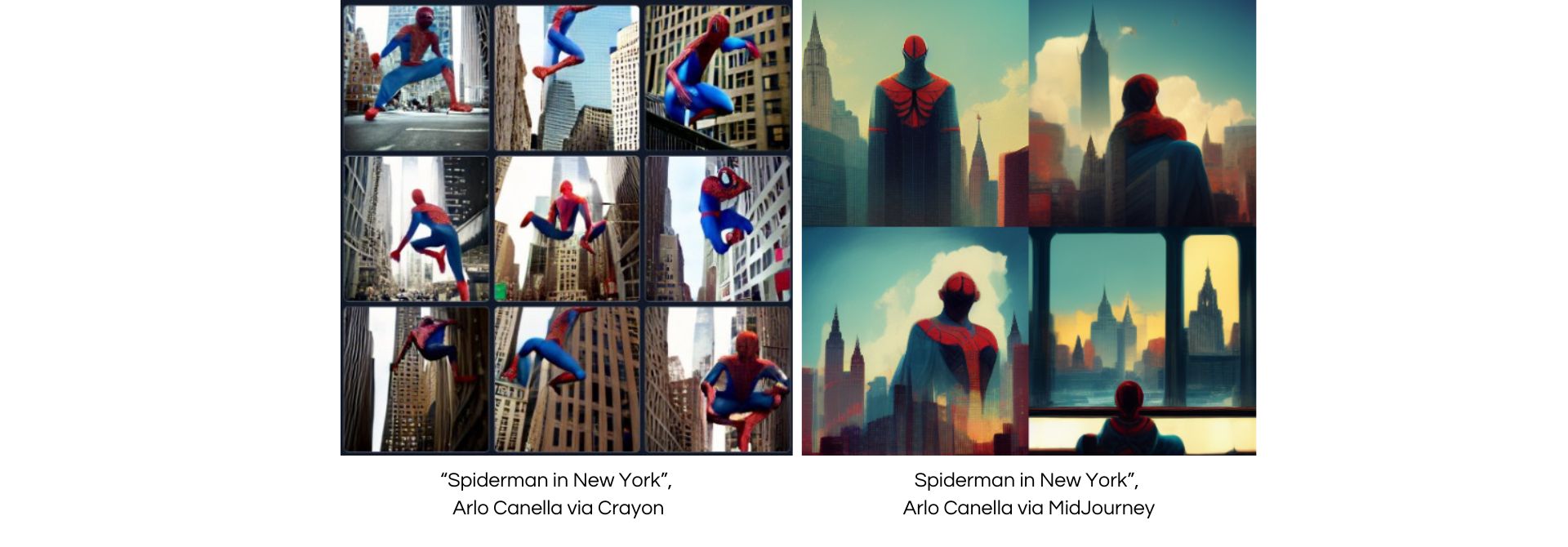

And yet this is not always the case. A character like Spider-Man, for instance, is a copyrighted work in its own right. I asked both Craiyon (formerly Dall-E) and Midjourney to draw “Spider-Man in New York” for me.

Well, if Midjourney seems to have taken care to make the character (whose rights now belong to Marvel-Sony) unrecognisable, the same cannot be said of Craiyon.

As long as creativity is based on the human intellect and its mnemonic abilities, it is only possible to speak of plagiarism-counterfeiting if the earlier work is actually recognised in the later one. Speaking instead of artificial intelligence, one must radically exclude the hypothesis of mere “inspiration”, which is potentially legitimate.

Frankly, software that creates and sells (or makes others sell) illustrations by exploiting other illustrations or photographs, even after having dismembered (and suitably reassembled) them, does not seem to be lawful. Not even under the American Fair Use or European Three Step Test.

In conclusion, as far as illustrators and other right holders are concerned, I can only remind them of one of the most important principles (which can even be traced back to the Berne Convention), namely to clearly claim their copyright on their work, in each and every online publication and reproduction, if possible also by applying appropriate technological means of protection as required by Articles 3 and 4 mentioned above.

© Canella Camaiora S.t.A. S.r.l. - All rights reserved.

Publication date: 11 October 2022

Last update: 7 May 2025

Textual reproduction of the article is permitted, even for commercial purposes, within the limit of 15% of its entirety, provided that the source is clearly indicated. In the case of online reproduction, a link to the original article must be included. Unauthorised reproduction or paraphrasing without indication of source will be prosecuted.

Arlo Canella

Managing Partner of the Canella Camaiora Law Firm, member of the Milan Bar Association, passionate about Branding, Communication and Design.