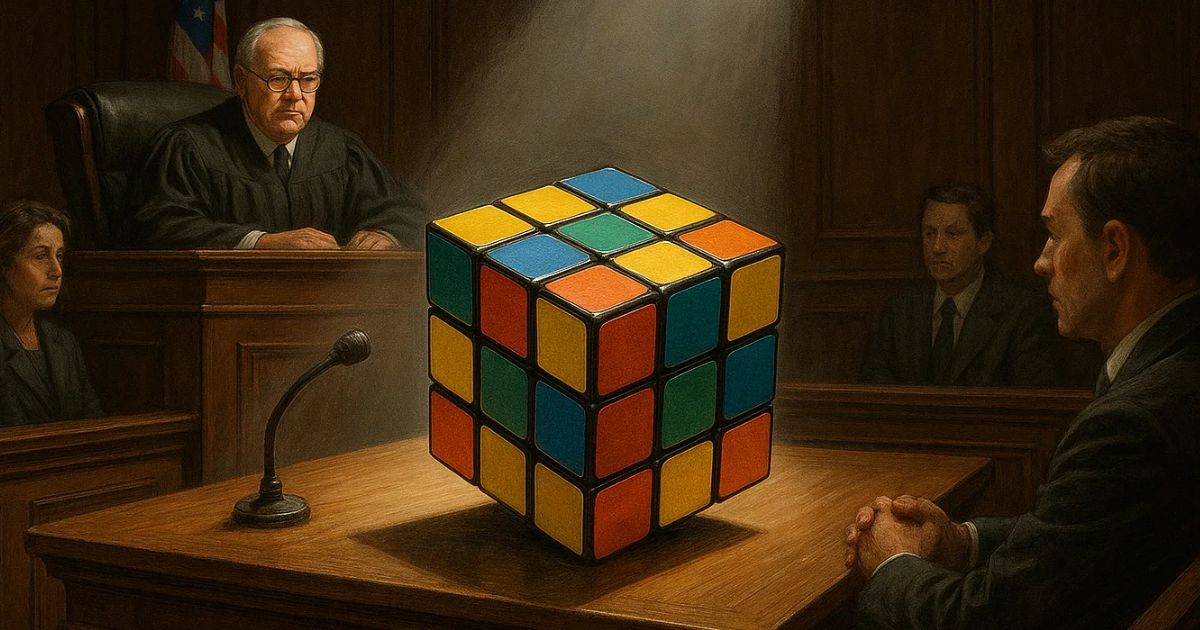

On April 30, 2025, the Venice Court prohibited the sale of a three-dimensional puzzle called the “Cubo Teorema,” judging it too similar to the famous Rubik’s Cube. The ruling recognized the protection of the Rubik’s Cube as a work of industrial design under Italy’s Copyright Law. But the most noteworthy element is not the outcome – which is hardly contestable – but the reasoning used to reach it. According to the court, copyright protection depends not only on the originality of the product but also on its alleged “artistic value”. And here lies a systemic issue.

“Artistic value”: a uniquely Italian standard

In Italy, copyright law (Law No. 633/1941 – LdA) stipulates that a design product – like a chair, a lamp, or a puzzle such as the Rubik’s Cube – can be protected by copyright only if it possesses two essential qualities: it must be creative, meaning the result of the inventor’s ingenuity, and it must also have so-called artistic value.

But what does “artistic value” mean? It implies that the object must not only be useful or original but also appreciated as if it were a work of art. Italian judges verify this through external indicators – for example, whether the object has been displayed in museums, awarded by art critics, cited in specialized books, or admired in cultural settings (see: Design and “regulatory schizophrenia”: when the true meaning of Art gets lost in the mesh of the Law – Canella Camaiora).

In short, being aesthetically pleasing or interesting isn’t enough – it must be publicly recognized as something of “high level”.

In the case of the Rubik’s Cube, this requirement was considered fulfilled due to its display at New York’s MoMA, its celebration in renowned publications, and its recognition as a symbol of the 1980s. Thus, the Venice Court found that artistic value existed, justifying copyright protection.

The question that naturally arises is whether this requirement was truly necessary. The “artistic value” standard is uniquely Italian and not required by EU law. Today, it risks being more of an obstacle than a safeguard. Not every creative object ends up in a museum, and not every designer has a powerful PR machine or historical recognition. As a result, newcomers or lesser-known creators may be excluded from protection – even if they have developed something original and worthy of copyright.

The EU position: originality and identifiability are enough

In the European Union, copyright rules are not solely decided by individual countries. There are common standards aimed at ensuring equal treatment for all EU creators.

The key rule is Article 2(a) of Directive 2001/29/EC, which grants authors the exclusive right to authorize or prohibit the reproduction of their works.

But what qualifies as a “work”? This is clarified by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), particularly in the well-known Cofemel judgment – Case C-683/17 (see: Design projects: how to pitch them “safely” to companies – Canella Camaiora).

In that ruling, the Court stated that a work is protected by copyright when it meets two requirements:

- originality, as it must be the author’s own intellectual creation, the result of free and creative choices;

- objective identifiability, meaning it must be clearly and precisely recognizable, without ambiguity.

Nothing more is needed. The Court firmly stated that Member States may not add further criteria – such as Italy’s requirement of “artistic value.” This is because introducing subjective filters, like assessments of artistic merit, would jeopardize legal harmonization and create unequal treatment for artists across countries. Originality is a legal concept, not a subjective or aesthetic judgment.

For this reason, Italy’s position – requiring “artistic value” to protect a design work – is inconsistent with EU law. Each time an Italian court applies this standard, as in the Rubik’s Cube ruling, it risks disregarding EU law.

In summary, according to the CJEU, if a work is creative and clearly identifiable, it deserves protection. No further evaluation is necessary.

A selective criterion that penalizes innovation

The fact that an Italian court, such as the one in Venice, still applies “artistic value” as a condition to protect design is concerning. Not only does it ignore EU rules, but it also creates legal uncertainty.

It means that an Italian designer must demonstrate their work is “almost a work of art” to receive the same protection that a German or French designer receives automatically. Achieving this often depends on external recognition – like museum exhibitions or features in specialist magazines – not on the author’s genuine creativity.

This risks excluding from protection precisely those who deserve it most: young creatives, small businesses, independent designers. Instead, it rewards the “usual suspects” – famous, celebrated, and widely distributed products. This is the case with the Rubik’s Cube, which obtained protection thanks to its iconic status.

This approach seems to hinder innovation, sending the message that having an original and useful idea is not enough; it must also please the critics.

But design isn’t just art – it’s function, intuition, and well-thought-out everyday objects. For this reason, it deserves clear, accessible, and inclusive legal protection.

Toward fairer and more modern protection

The Venice Court’s ruling reminds us that, in Italy, copyright in design is still tied to an outdated and restrictive view – one that looks to the past rather than the future. Requiring an object to be “artistic” is not mandated by EU law and often becomes an unjustified filter.

To be clear, no one doubts that the Rubik’s Cube deserves copyright protection – it’s a brilliant, original, and universally recognizable idea. But – and this is the point – it would still deserve protection without needing to pass the “artistic value” test. Adding unnecessary requirements, as Italian law does, diverges from EU standards and makes protection harder to obtain for many other design objects.

Copyright should promote creativity – not build entry barriers. Europe has chosen a clear path: what matters is originality and clarity, not aesthetic judgments or fame.

It’s time for Italian law and jurisprudence to move forward – not to abandon design protection, but to make it fairer, more modern, and aligned with the real world of today’s designers.

Design belongs to everyone. And it deserves a legal framework that recognizes it—without unnecessary filters.

© Canella Camaiora S.t.A. S.r.l. - All rights reserved.

Publication date: 3 June 2025

Last update: 11 June 2025

Textual reproduction of the article is permitted, even for commercial purposes, within the limit of 15% of its entirety, provided that the source is clearly indicated. In the case of online reproduction, a link to the original article must be included. Unauthorised reproduction or paraphrasing without indication of source will be prosecuted.

Margherita Manca

Lawyer at The Canella Camaiora Law Firm, member of the Milan Bar, she specialises in industrial law.